¿Why is Sarmiento in boston?

Introduction

“You have to visit the Sarmiento statue once you get there.” My friend's grandfather said this to me during a farewell dinner when I told him I was leaving Buenos Aires and going to study education at Boston College. Born and raised in China, then having spent seven years in Buenos Aires, I am used to seeing different cultures being represented in distinct parts of the world. However, it still intrigues me why there was a Sarmiento statue in Boston, a Latin American educator and president in the 1800s, in the city with a high concentration of higher education institutions.

Apparently, my curiosity was shared by the Argentina national soccer team. My friend’s grandfather described that when he worked as a football commentator, he accompanied the team to visit the US during the 1994 World Cup, and that was the first time he saw the Sarmiento statue in person: “Of course, we had all the curiosity in the world, just like all the other Argentine people when they visit. Perhaps the Americans don’t feel represented as much, and they may ask who he [Sarmiento] is. Well, for us, the Sarmiento bust sent from Argentina to the US was something very distinctive.”

After hearing about this, I tried to recall what I had learnt before about Sarmiento in my Argentine history classes, but nothing really came up other than the fact that he was both an educator and a president at the time. Therefore, there must be a reason why he was so important to have a place on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. There is clearly a connection between Argentina and the US here. This led me to visit the Statue myself several weekend afternoons and begin a further investigation.

Methodology

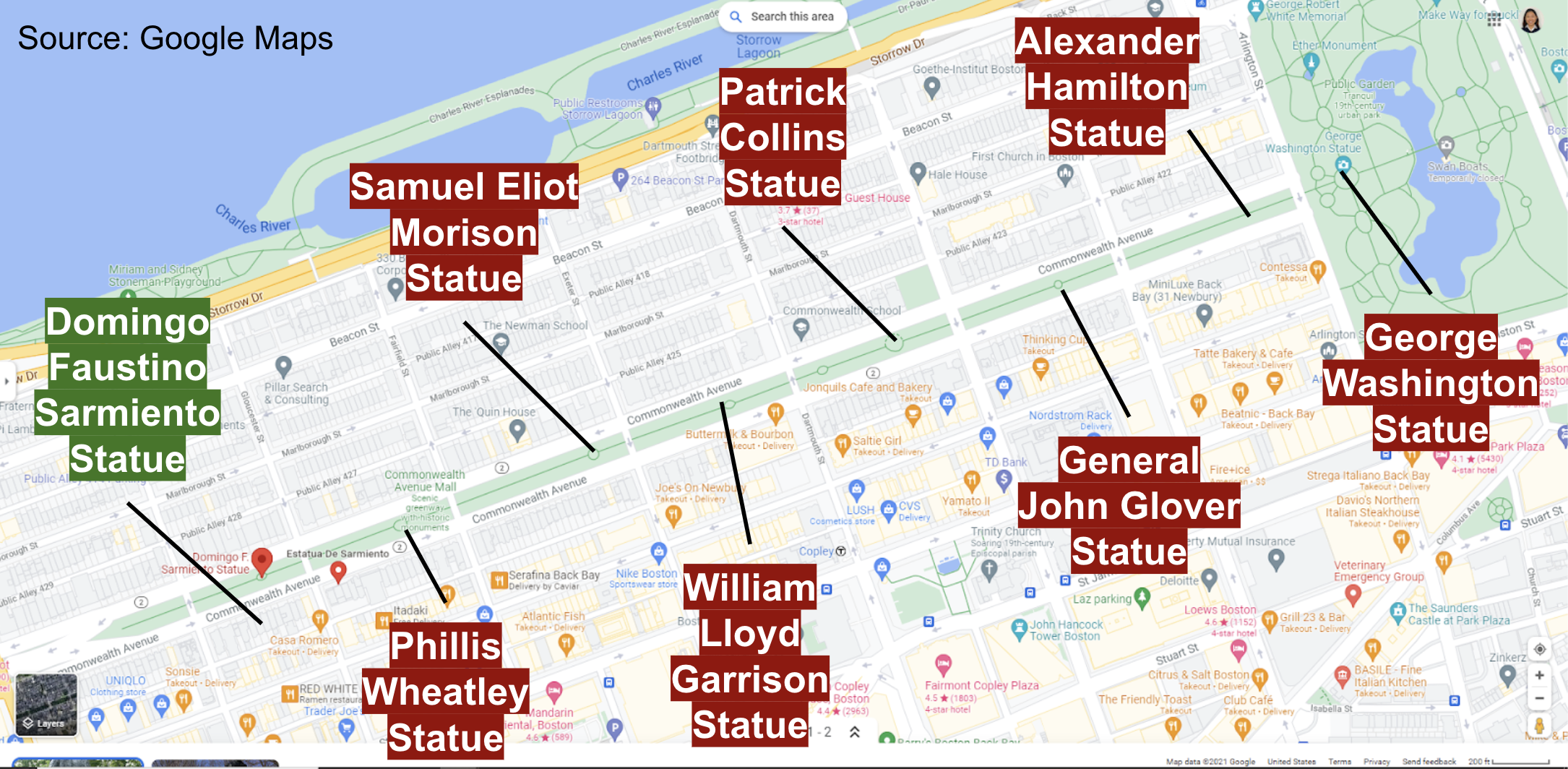

Starting from the George Washington Statue in the Boston Commons, I walked down Commonwealth Avenue until I reached the Sarmiento Statue which is the last one established in the park area. In between, I passed through statues of prominent figures in American history: war heroes, founding fathers, political figures, etc. The only non-white figures are the last two on the avenue: Phillis Wheatley, the first African American author to publish poetry (O’Neale, 2021), and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, the Argentinian educator, ambassador, and president.

In comparison to the parallel Newbury Street, a central commercial district with large pedestrian flow and tourist visits, Comm. Ave. holds more tranquillity and many local people enjoy their walks accompanied by their pets or simply spending some cozy time on the benches on the sides. Although the pedestrians all curve around the statues to follow the path, very few of them actually stop to read the information plates, and even fewer stop by the Sarmiento Statue. I interviewed various people around the statue on a Saturday afternoon, and most answers I got were “I’m sorry I don’t know who that is”. I was surprised to hear one person saying “I think he’s someone from Argentina right?” and I actually had the opportunity to tell people about Sarmiento when they said “I don’t know anything about it but I’d love to because I always come here.

It’s true that the Sarmiento statue is described as “Boston’s lesser-known statues” (Ryan, 2021) and on the Google Maps page, there aren’t any comments under the statue’s page. But for me, this statue holds a lot more weight and should receive more recognition not only because of Sarmiento’s impact on Argentina’s development centuries ago but also because of the ideologies he brought back to Argentina that later became a symbolic tie between the two countries, which also helps us understand why the world works as it is nowadays.

Connecting this topic to the content of the course, I will refer to the historical research with the chapter on Progress (Chasteen, 2001) and reflect on the ideas of how Argentina developed a more progressive society focusing on the impact of a newborn educational system. Also, I will talk about the socio-cultural aspect connecting to the idea of “Civilization and Barbarism” (Swanson, 2000) that was proposed by Sarmiento in his project intending to “civilize the whole population.”

Throughout this essay I will try to answer the question of “How significant was Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s experience as both an ambassador and an educator in the US on shaping the Argentinian public education system?” by conducting a historical study. I will analyze what were these ideologies that Sarmiento learnt from the educator Horace Mann during his stay in Boston at the beginning of the 1800s, and how those approaches work differently in distinct social contexts at that time. Also, I will research how the US Educational Reform inspired Sarmiento to bring civilization to Argentina as well, taking into account the different levels of social development of both countries at the time. Furthermore, I will argue that even though his educational ideologies transformed Argentine society with the aim of promoting civilization, the means used to achieve it (civil war, wiping out indigenous population) contradict the goal.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento

Sarmiento “liked to say that he was one year younger than the Republic, since 1811 was the year after Argentina declared its independence and initiated actions which ultimately drove the Spaniards from that part of the New World.” (Rockland, 1970) His birth marked the start of a “progress” period of history, where the Argentinians searched for self-identity and the notion of a “nation”. Born in the rural fringe of San Juan in 1811, Sarmiento was “nurtured on a biography of Benjamin Franklin.” (Stewart & Mashal, 1940) who as an educator inspired Sarmiento to later pursue his career in education. During his twenties, Sarmiento suffered from the reckless rule of Juan Manuel de Rosas, a caudillo who violently appropriated lands leading civil wars. Therefore, in 1831 Sarmiento crossed the borders to Chile first working as a journalist, and officially started his career as an educator. He first founded the first normal school in South America in 1842, after evaluating the importance of education in literary works. One of his most famous pieces, “Civilización o Barbarie” (Sarmiento, 1845) was written during this time.

In 1845, Sarmiento sailed to Europe under the instruction of the Chilean government (Crowley, 1972) to further his study of public instruction. On this trip, Sarmiento visited different schools and evaluated school systems in various countries. But most importantly, it was during his travels when he first encountered Horace Mann through one of his reports as the Board of Education. In his book Educación Popular (Sarmiento, 1896) Sarmiento said “After this important work fell into my hands, I had a fixed point to which to direct myself in the United States.” This sets the foundation for his journey to the US in 1847 the development of his lifelong friendship with Horace Mann.

Sarmiento in the US

The US in the 1800s

It is said that during the beginning of the 19th century that there was a significant “paradigm shift from privileged, religiously-based education to common, state-sponsored education” (Wright, 2019) Ever since the colonial period, the ecclesiastical institutions held great powers because they were in charge of educating the population. The core curriculums taught by the Catholic Church consisted of how to read the Bible, and their principal aim was to teach the young about the main moral values of the scriptures.

The first ideas about educating children to be good citizens in the future started with the birth of public education, where the state uses taxes to fund educational institutions separated from the Catholic church. The first public schools in the US were established in the area of New England. The oldest public school ever founded was Boston Latin School, which was built based on the model of British grammar schools (O'Donnell, 2021). The first public high school was The English High School (Wright, 2019), which also followed the model of The Royal High School in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Moreover, after the American Revolution, the notion of “Republican Motherhood” was also introduced, where “in the wake of the war women found themselves in the new Republic without a clear political role and so they shifted their political energies to nurturing civic virtue in their sons and daughters.” (Kerber, 2016) This aligned with Sarmiento’s ideology because he considered women as natural caretakers of children and are key figures in educating the future generation. We will see in later chapters how he accomplished this concept in concrete actions by bringing American female teachers back to his homeland aiming to spread the spirit of women’s freedom.

Educational ideology

Similar to Sarmiento, Horace Mann was also born in a family of poverty and received little education. Raised in Franklin Massachusetts, Mann self-taught and was admitted to Brown University. (Anonymous, 2014) At Brown, he recognized how education should be more accessible since it’s a powerful tool for social progress. As the valedictorian of his class, Mann delivered his graduation speech with the theme of “The Progressive Character of the Human Race” (Winship, 1924) He highlighted how “education, philanthropy, and republicanism.” (Anonymous, 2014) will bring advances. Horace Mann started his career in politics first serving in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and later as the president of the senate. “During these years, Mann aimed his sights at infrastructure improvements via the construction of railroads and canals and established an asylum for the insane at Worcester.” (Anonymous, 2014) Here we can already see his ideology of doing good for the common people and improving social inequality through infrastructural improvements.

In 1837, Horace Mann was elected secretary of the Board of Education of Massachusetts as part of the movement of Educational Reform. “As part of his campaign to establish quality education for all children, Mann played a key role in the founding of the nation's first teacher training institute, which opened in Lexington in 1839. ” (Anonymous, 2021) Like Sarmiento, Mann also traveled to Europe to observe the Prussian education system. Mann returned enlightened and determined, and he developed his principles about public education:

(1) citizens cannot maintain both ignorance and freedom; (2) this education should be paid for, controlled, and maintained by the public; (3) this education should be provided in schools that embrace children from varying backgrounds; (4) this education must be nonsectarian; (5) this education must be taught using tenets of a free society; and (6) this education must be provided by well-trained, professional teachers. (Anonymous, 2014)

That was also the start of “The Common School Movement” (Anonymous, 2021). Under the context of a paradigm shift from a church-owned education system to a publicly funded free education, the principles were innovative yet controversial at the time, since the religious institutions opposed the lessening importance of religion in school and the diminishing power and authority the church had over the citizens.

In the midst of this change, Sarmiento decided to visit the US in 1847. His encounter with Horace Mann was not smooth despite their passion for education: “Mann knew no Spanish and Sarmiento essentially no English.” (Rockland, 1970) However, Mary Mann took the role of translator, communicating with Sarmiento in French. During this exchange, Sarmiento was mesmerized by Mann’s wisdom:

Mann did not give Sarmiento new ideas so much as he confirmed in him ideas already present and slowly gathering strength: a democratic political and social context was the best atmosphere in which education might flourish, and that an educated populace was the greatest resource upon which a nation might draw. (Rockland, 1970)

This quote will be very important because it defined the ideologies that Sarmientos followed to implement his own policies of educational reform once he returned to Argentina.

Sarmiento in Argentina

Education constructing society

Due to the politically tumultuous environment in Argentina, Sarmiento’s first stop back from the US was Chile, where he founded the first normal school in South America. It was not until 1855 when he decided to stay in Argentina and devote himself to bringing a change in the field of politics. He was first elected to be Director of School in his hometown San Juan and later won successive elections in the National Congress as a Senator representing San Juan. In 1862, he became the governor of San Juan. During this time, he set the foundation for his dream to bring education to all, and followed Horace Mann’s footsteps, building infrastructure to benefit the population: improvement in the transportation systems such as the train, better communication such as telegraph lines, new hospitals, and most importantly, new schools. Sarmiento founded “an agricultural school, a preparatory school, and a national college” (Stewart & Mashal, 1940) In 1875, Sarmiento sanctioned “Ley de Educación Común y Obligatoria” (Law of common and obligatory education) which demands a mandatory alphabetization of all the children of the republic through the public school system. (Lionetti, 2020) However, the most important step he took to bring civilization was by directly bringing the American teachers to Argentina.

Las maestras norteamericanas

In 1865, he returned to New York and heard about Mann’s death in 1859. He wrote a letter to Mary Mann to express his lament, and through this exchange of letters, they were able to continue developing their friendship further. There have been “176 Sarmiento letters and 195 Mary Mann letters” found (Rockland, 1970) which shows their deep relationship throughout the years. This relationship becomes significant because years later when Sarmiento sent a copy of his book Facundo o Civilización y Barbarie to Mary Mann, he reflects on the Bostonian system and its difference with South American education:

Spaniards did not follow the wise policy of your New-England ancestors in establishing schools to continue, through them, the civilized practices and traditions of Europe. This circumstance explains about one-half of those civil wars now raging among their descendants. (Rockland, 1970)

This links again to Sarmiento’s view on the function of education. According to him, education systems should develop citizens who carry on the traditions of civilizations, in other words, the European traditions. This sparked the project he initiated ever since he was elected president of Argentina in 1868: to bring civilization from the US to Argentina. Between 1869 and 1898, Sarmiento brought approximately sixty-one teachers from the normal schools around the US to the interior provinces of Argentina. (Zeiger, 2021) First of all, Sarmiento’s intention was to bring the colonial influences (British and Scottish) that shaped the public education system founded by Horace Mann in Argentina as well. And secondly, after witnessing women’s freedom in American society at the time compared to Argentina, Sarmiento believed that women achieve their freedom through autonomy, and one of the ways is to use their natural gift as caretakers to develop their vocation in the field of education. (Zeiger, 2021) Again, this links to the notion of beginning progress into society and empowering women to subvert the traditional views of society.

However, this second point is arguable from a modern perspective. On the one hand, and on the surface level, encouraging women to be educators because of their natural abilities as teachers, reflects a positive and progressive society at that time: giving women an opportunity to find their place in the workspace, and empowering them to find autonomy without being dependent on the men in society. However, on the other hand, this reflects the other side of the society’s values and ideologies regarding women’s role in society. By putting them in the position of teachers, women are put under the socially constructed gender role and further deepen it. According to Philip Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland, “We’re not beyond having a cultural devaluation of women’s work so that if a job is done primarily by women, people tend to believe it has less value.” (Rich, 2014) Thus, does this offer an explanation for the lack of attention paid to education in general during the 1800s? Leading this topic one step further, was Sarmiento’s idea of an educational reform taken more seriously because of his identity as a man? These are questions that will only serve the purpose of reflection because of the distant historical context. Of course, the notion of feminism didn’t exist yet during the time of Sarmiento, but as a contemporary scholar evaluating this issue, it’s interesting to apply modern lenses to look at different perspectives.

Civilización o barbarie

Sarmiento’s attitude toward the gauchos and the indigenous population was described by Philip Swanson, professor of Hispanic Studies as to “consolidate a precarious sense of order, progress and modernity (usually associated with the emerging urban metropolises) in the face of a perceived threat of instability from the supposedly wild, untamed, chaotic masses (associated largely with the undeveloped interior.) (Swanson, 2000) It’s interesting how the author used the phrase “precarious order” because it accurately describes the nature of this ideology: achieving order through making the indigenous population assimilate to European-style metropolitan life.

As mentioned earlier, Facundo o Civilización y Barbarie is probably the most well-known work of Sarmiento, it is the book that carried the core of his ideology. He viewed education as a tool to transform society and progress into modernization; this would allow Argentine society to move from an agricultural-dominated society to an industrialized one. In order to modernize the country, building schools and developing trained faculty members with the help of North American educators was one of the ways. Another way of carrying out this ideology was through civil war and fighting barbarism using barbarism.

In 1864, under the presidency of Bartolomé Mitre, Argentina joined the Triple Alliance and declared war against Paraguay (Smink, 2020). This was considered the most violent war in Latin American history because of the tremendous number of casualties that resulted. The coldest part of this, however, is that the Argentine government purposely sent the gauchos to the frontline. This is a clear demonstration of the social segregation and discrimination of the gauchos, and that political power can cruelly decide to sacrifice the “barbaric” native people and mestizos instead of the “civilized” European descended army. During the war, Sarmiento was visiting the US and was anxious not because of the atrocity happening back home, but because of the US newspaper’s portrayal of Francisco Solano López (the Paraguayan president at the time) as a war hero and the US population’s sympathy toward Paraguay:

Sarmiento, distressed over what he read in American newspapers, worked to counteract what he regarded as the myth of the heroic López. He published articles in the New York Tribune and the Boston Daily Address in order to present his country’s views of the conflict. (...) “The newspapers find it useful, sensational” he wrote, “to be in favor of those savages. It is useless to show them the truth.” (Brandt, 1962)

Paraguay had a high percentage of assimilated indigenous population due to former president Carlos Antonio López’s policy thus explaining why Sarmiento referred to the Paraguayans as “those savages.” (Reber, 1988) Therefore, it is impossible to not see Argentina’s participation in the Triple Alliance as racially motivated.

A decade later, this time under Sarmiento’s presidency, general Julio Argentino Roca (Brudney, 2019) led the Conquista del Desierto (Conquest of the Desert). This was an expansionist and nationalist campaign into the Pampas area with the aim to unify the territories. From 1878 to 1884, the military invaded indigenous people’s land in southern Argentina, mainly in the Patagonian desert (thus the name). What’s more, they killed thousands of native people:

Roca's 6,000-strong cavalry force crushed Mapuche and other Indian groups, killing more than 1,000 and capturing thousands more who became servants or prisoners and were prevented from having children. Campaign dispatches depicted them as barely human. White settlers turned the conquered lands into a breadbasket which made Argentina an agricultural superpower and a confident, thrusting nation in the early 20th century. (Carroll, 2011)

This tragedy is a clear parallelism to the Manifest Destiny policy in the US during the same time period (Prevost, 2011). The US felt the responsibility to “illuminate the world” for religious reasons - they were destined by God to bring civilization to the West and unify the country from coast to coast. This is also a very clear parallelism to the beginning of the Spanish colonization in the American continent, because their aim of the voyage was also to spread the religious ideas to another continent. However, this is not justifiable for the massacre of the native people who have been living on their land for centuries.

Personally, I think it is a very debatable topic whether one group of people can decide what is considered “good” for the rest of the population. It is especially ironic the idea of achieving civilization and building a nation as a whole, by using barbaric methods. Asedon the historical instances of violence, the figures of authority should not decide that they have the right to “enlighten” or “educate” others. Especially when violence is involved. I don’t think the means justify their goal because during the expansion of the US territory, native Americans lost their identity, they suffered a violent genocide and were forced to “be progressive”.

Conclusion

It’s hard to define anyone with a reduced concept like “a good educator” or a “bad president”, but it is fair to say that although Sarmiento was not the most popular president in Argentine history, he did indeed bring a better public education system to the society at the time. His conversations with Horace Mann and Mary Mann brought an enlightened perspective on the education system for Argentina. Moreover, the result of an established education system and laws to enforce it is still evident until today: “Education in Argentina is obligatory, which implies that pupils must attend the school chosen by their parents among the alternatives offered by those schools recognized by the State, whether state-managed or privately-managed” (Chavez, et al. 2012).

In the process of writing this essay I gained a deeper understanding of not only the Argentine culture, but also the construction of the Latin American culture as a whole. Especially with the topic of feminism which was an extension conversion from the “Maestras norteamericanas” and “Civilización o Barbarie”. I learned that there are always dichotomies to look at something: bringing female teachers to Argentina meant better human resources in the education system but also created a stereotype in the workplace for women, that they could only be educators and caretakers; the intention of bringing modernization and civilization to the whole country can result in the destruction of native cultures, social segregation and death.

Connecting ideas to Mill’s theory of the relationship between “troubles” and “issues” (Mills, 2000) to a certain extent Sarmiento’s policies toward the indigenous people can be analyzed with this theory. As mentioned in the essay, during the majority of his young adulthood he was forced to move from place to place because of the violent rule of the caudillos. His exile to Chile was the turning point where he had the safety and freedom of speech to express his discontent about the caudillo system, thus the birth of Facundo, literally named after a caudillo. However, whilst in power to make a change in the social structure, by putting all the caudillos and gauchos and the native people living in the interior in the same box, Sarmiento overlooked the implications of his decisions. Perhaps his personal matters in the past (“troubles”) escalated into a structural and systematic problem (“issue”).

Considering the bigger framework of the sociological imagination, looking back at this relatively distant history also helped me to comprehend how we, human beings, have the power to modify society and history with social constructions and ideologies. Sarmiento’s ideologies were developed under multiple influences that may be hard to understand for us because we live in very different worlds. My perspective as an academic researcher in the twenty-first century already means that I have a particular lens looking at the past.

Now each time I have the opportunity to walk past Sarmiento’s statue on Commonwealth Avenue, I will look at it through a more skeptical and cynical lens. And if I ever start a conversation with people who sit around about the statue, it will be more than just “I know he’s someone from Argentina.”

References

O’Neale, S. (2021) “Phillis Wheatley” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Ryan, J. (2021) “Boston’s lesser-known statues” Boston.com, http://archive.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/gallery/boston_statues?pg=7. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Chasteen, J. (2001) “Progress” Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America, Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc, https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393283051/about-the-book/description. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Swanson, P (2000) “Civilization and Barbarism” The Companion to Latin American Studies, Oxford University Press, https://irm.bc.edu/reserves/sc036/more/sc03629.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Rockland, M. A. (1970). Sarmiento’s Travels in the U.S. in 1847. Princeton University Press, https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691647616/sarmientos-travels-in-the-us-in-1847. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Stewart, W. & Mashal W. (1940). The Influence of Horace Mann on the Educational Ideas of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. Duke University Press, https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article/20/1/12/156189/The-Influence-of-Horace-Mann-on-the-Educational. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Sarmiento, D. (1845). Facundo o Civilización y Barbarie. Biblioteca del Congreso de la Nación, https://bcn.gob.ar/uploads/Facundo_Sarmiento.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Crowley, F. (1972). Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. Twayne Publishers, https://bc.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/410420. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Sarmiento, D. (1896). Educación Popular. Editorial Universitaria, http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/unipe/20171121060454/pdf_346.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Wright, C. (2019). “History of Education: The United States in a Nutshell” Leader in Me, https://www.leaderinme.org/blog/history-of-education-the-united-states-in-a-nutshell/. Accessed October 28, 2021.

O'Donnell M. & Al Ibrahim K., (2021). “Boston Latin School,” Boston History, https://explorebostonhistory.org/items/show/30. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Kerber, L. (2016). Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary American. University of North Carolina Press, https://www.amrevmuseum.org/read-the-revolution/women-of-the-republic. Accessed October 28, 2021.

Anonymous. (2014). “Horace Mann Biography” A&E Television networks, https://www.biography.com/scholar/horace-mann.

Winship A.E. (1924). “Horace Mann, personally and professionally - (II.)” The Journal of Education, Vol. 100, pp 481-483, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42749316.

Anonymous. (2021). "The Education Reform Movement." American Social Reform Movements Reference Library, Encyclopedia.com, https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/education-reform-movement.

Zeiger, C. (2021). “La historia de las maestras estadounidenses que Sarmiento trajo a la Argentina” Página 12, https://www.pagina12.com.ar/347201-la-historia-de-las-maestras-estadounidenses-que-sarmiento-tr.

Rich, M. (2014). “Why Don’t More Men Go Into Teaching?” The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/07/sunday-review/why-dont-more-men-go-into-teaching.html.

Lionetti, L. (2020). “Sarmiento en la Dirección General de Escuelas. Disputas y negociaciones con las comunidades de la campaña bonaerense” Dirección general de cultura y educación, https://cendie.abc.gob.ar/revistas/index.php/revistaanales/article/view/119/582.

Smink, V. (2020) “150 años de la Guerra de la Triple Alianza: cómo fue el conflicto bélico que más víctimas causó en la historia de América Latina” BBC news, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-51678880

Brandt, N. (1962). Don yo in America: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s Second Visit to the United States 1865. The Americas, 19(1), 21–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/979404

Reber, V. B. (1988). The Demographics of Paraguay: A Reinterpretation of the Great War, 1864-70. The Hispanic American Historical Review, 68(2), 289–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/2515516

Chavez, H., Agrelo, R. & Candal, C. S. (2012). Argentina. In C. L. Glenn & J. De Groof (Eds.), Balancing freedom, autonomy and accountability in education: Vo. 3 pp 19-33. Wolf Legal Publishers.

Mills. (2000) The Promise. The Sociological Imagination. Vol. 1, pp 1-44. Oxford University press.

Brudney, E. (2019). Manifest Destiny, the Frontier, and "El Indio" in Argentina's Conquista del Desierto. Journal of Global South Studies 36(1), pp 116-144. University Press of Florida, https://doi.org/10.1353/gss.2019.0006.

Carroll, R. (2011) “Argentinian founding father recast as genocidal murderer”. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jan/13/argentinian-founding-father-genocide-row

Prevost. (2011) U.S. - Latin American Relations. Latin America: An Introduction. Vol.1, pp 316-340. Oxford University Press.